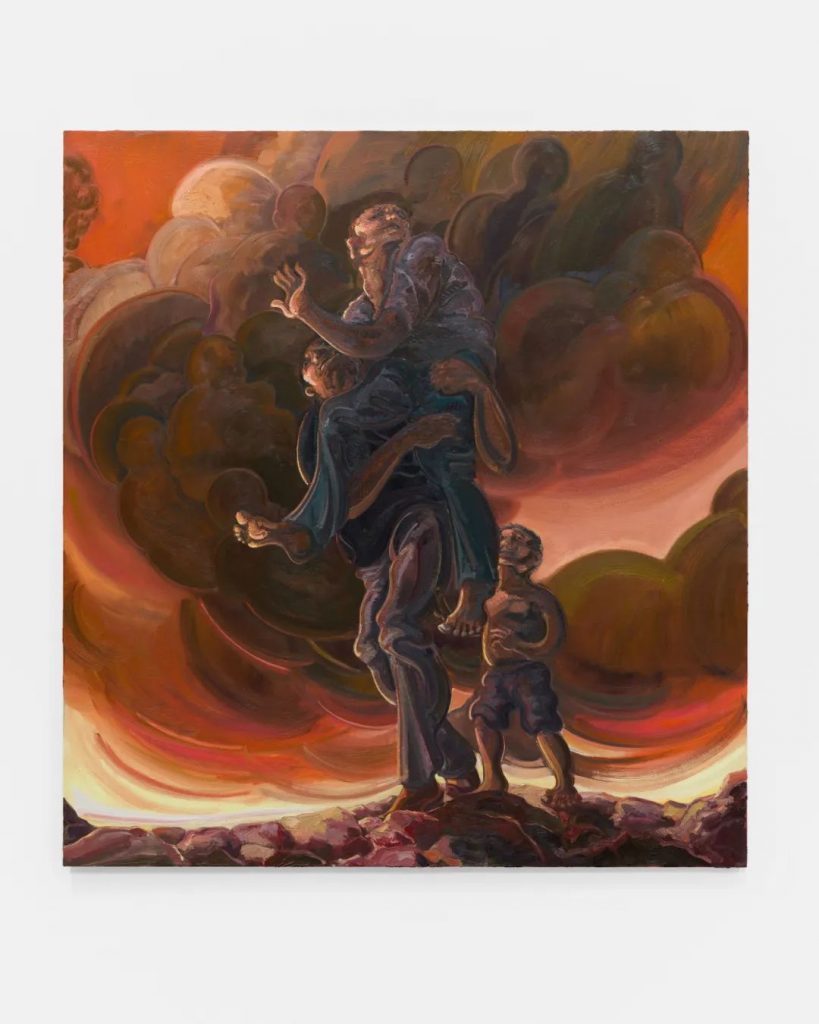

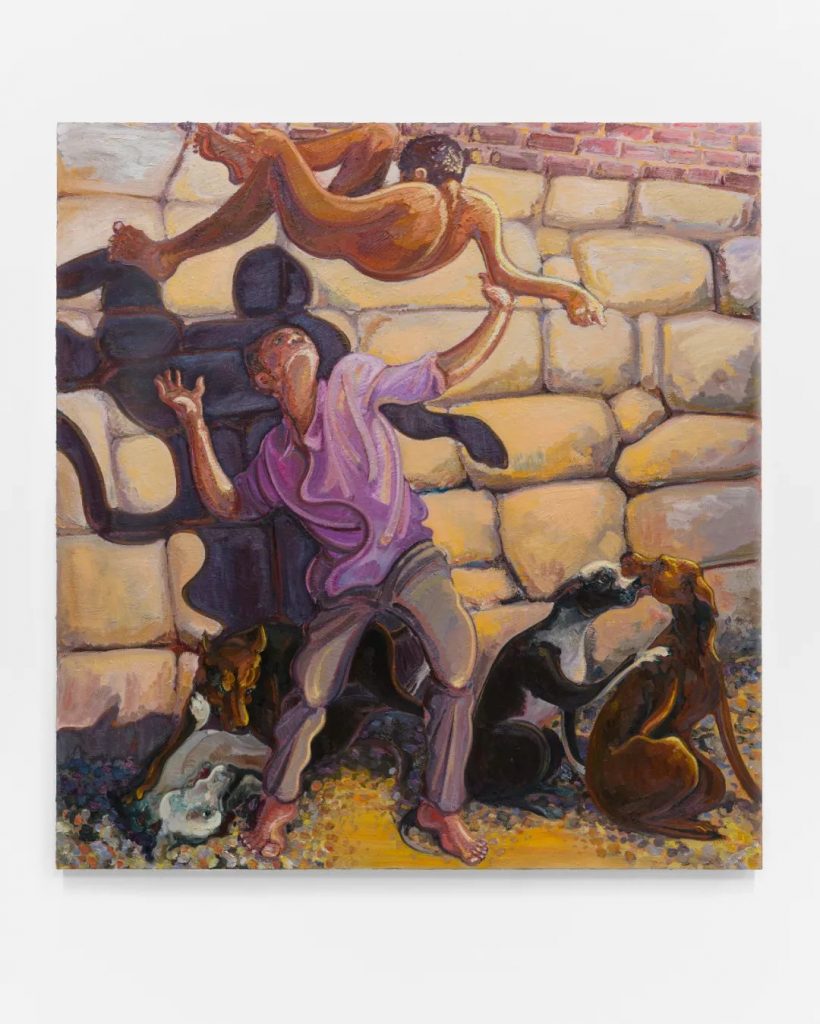

Timothy Lai, Father, Father’s Father, and Child, 2022, oil on canvas, 228.6 x 213.3 cm. Collection of Longlati Foundation. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Barrett

Conflict and flow are the consistent tone of Timothy Lai’s works. Between the twisted and squeezed flesh, we can glimpse the tension under the highly saturated hues, and along with the subtle changes in light and shadow, a different mood emerges on the screen. This language is most directly present in his deconstruction and reproduction of classical art. For example, in Father, Father’s Father, and Child (2022), he appropriates Italian artist Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s work Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius (1618-19), when the Greeks burned and looted the city of Troy after attacking it with the Trojan Horse, Aeneas, seeing that the situation was over, rushed to carry his aged father, Anchises, and fled the fallen city of Troy with his young son, Ascanius, with the help of Venus, the goddess of love (see Aeneas Runs Away from the Burning Troy, Fédéric Balocci, 1598). In the sculpture, Aeneas is fully muscled, in contrast to his thin, bony, sagging-skinned old father, who carries him on his shoulders. The artist invokes this allusion, but in a formal reference to another work by Bernini, The Rape of Proserpina (1621-22), where the three with very different looks intertwine, contradicting the inherent intergenerational relationship. On the other hand, the dynamic state embedded in Bernini’s sculptures is presented in Timothy Lai’s works with increasingly distorted strokes and gestures. Today, as the postmodern state of global mobility is combined with personal experiences, ethnic cultures and regional histories, such appropriation and reference are further revealed, and at the same time, the subject of discussion becomes more mixed and distorted.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Rape of Proserpina, 1621–1622, Borghese Gallery and Museum, Roma (left) Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Rape of Proserpina, 1621–1622, Borghese Gallery and Museum, Roma (left)

Federico Barocci, Aeneas Fleeing from Troy, 1598, Borghese Gallery and Museum, Roma

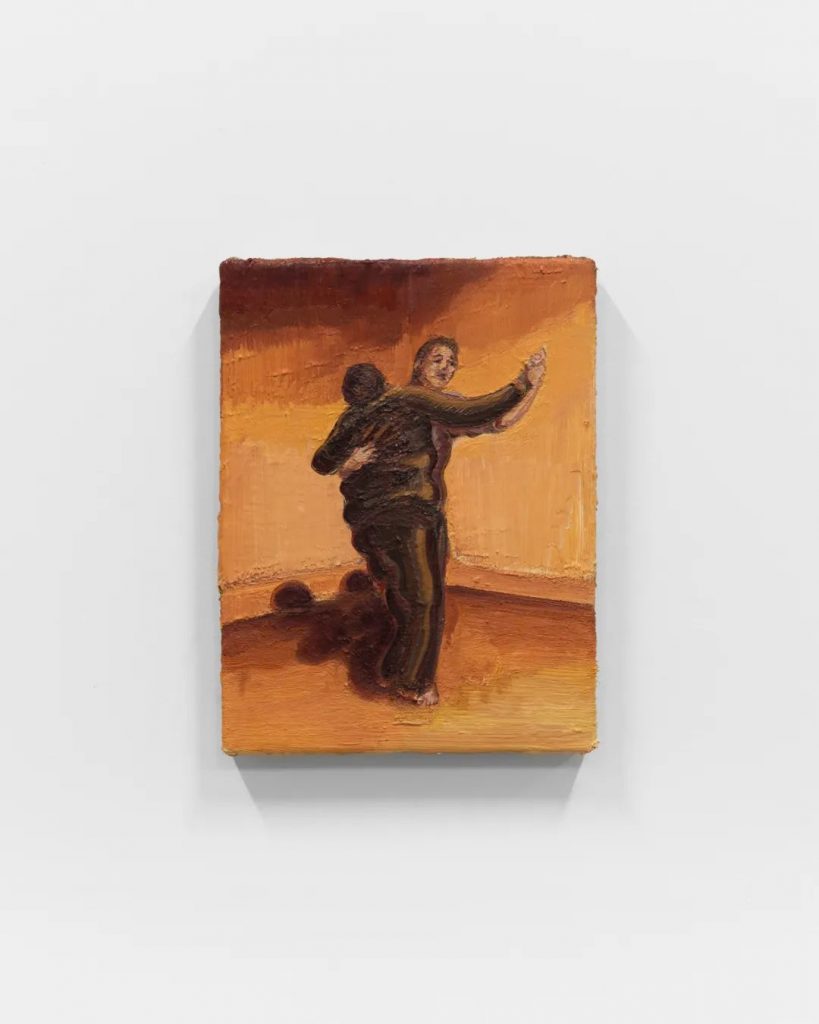

Timothy Lai’s tracing of Western art history has produced a continuous agitation in the collision with his identity background. As in most East Asian families, the relationship between father and son often leads to family conflicts, and the anxious atmosphere caused by such ties becomes even more irreconcilable when the family is in an immigrant environment. In the concordance of To Dance with My Father (2022), Lai seems to explain the fatalistic view of “like father, like son” and the inheritance that flows in the bloodline. In the emails exchanged with him over the air, Lai does not make a didactic general statement that “patriarchy is bad”, but rather observes and expresses the problems that arise from patriarchy at different stages of historical evolution, and the complexity and nuances that these problems lead to in spaces with different cultural backgrounds. In this way, the artist’s own position further reflects his entanglement, struggle, and discrete relationship with patriarchal culture. On this premise, he chooses to draw on the concept of family and clan, which is referred to by religious theological intent, to sort out the patriarchal thinking inherited therein, and to explore and translate the persistent influence of this ineffable intergenerational relationship diffused in contemporary society.

Timothy Lai, To Dance with My Father, 2022, oil on canvas, 30.48 x 22.86 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Barrett

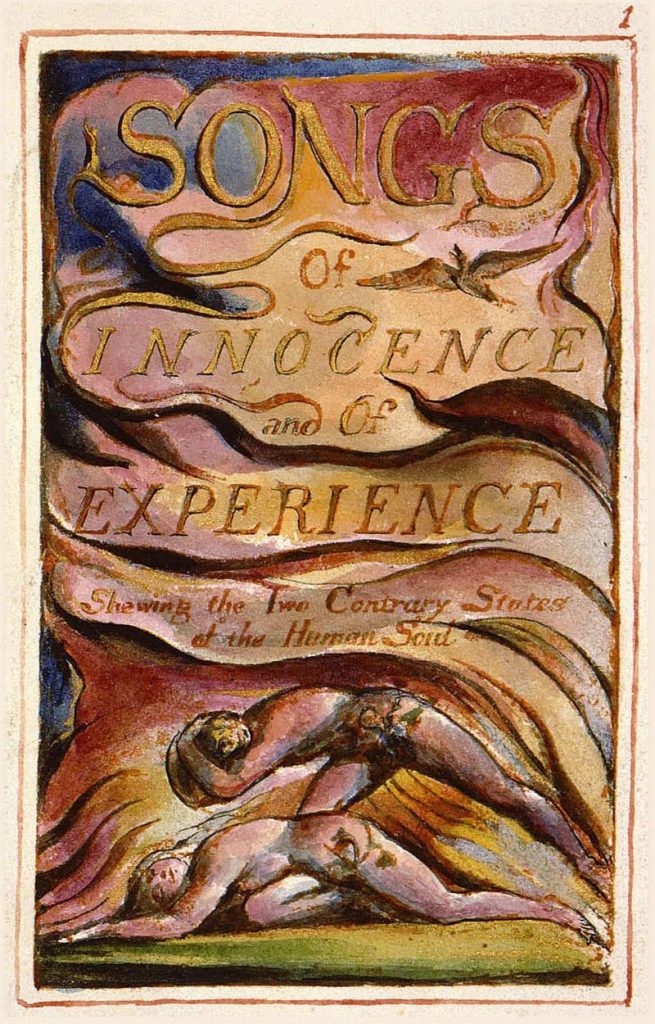

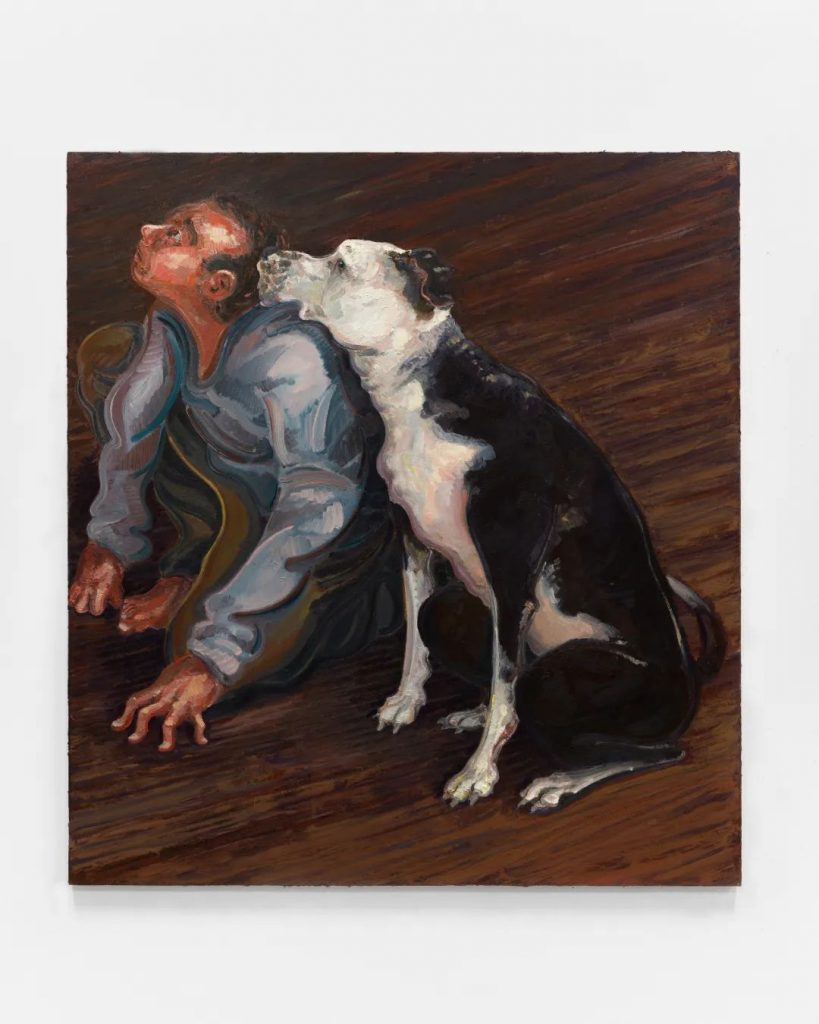

If the previous works presented a de-escalating father-son relationship, in the exhibition’s eponymous work Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me, Pa-1&2 (2022), Lai draws on the 1974 song “Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me,” written by the British musician Elton John, to provide a reason for the trauma that follows. Drawing on William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1789), he uses an etching from the book to convey the emotional and material dependence and passive relationship of a child to his father. Lai’s elevated perspective exaggerates the large adult male figure in contrast to the smaller and smaller boy on his shoulders. At the same time, the boy and dog in The Obedient (2022) are more direct in terms of character volume and pictorial structure, highlighting the artist’s innermost thoughts, such as “What defines a good son? What are the qualities that determine ‘what is a good son’? Who defines it? Whose will is imposed on the son?” In Timothy Lai’s own words, he argues that some of the logic and criteria evoked by these questions apply in parallel to the pet, but at the same time, the son/pet is treated with complete love and care. In the structure of the picture, both objects (the son and the dog) aspire to a role beyond their own framework, which further reinforces the childhood experiences and family ties that the artist possesses that he remembers.

Timothy Lai, Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me, Pa—1&2, 2022, oil on canvas, 244 x 152.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Barrett

Elton John, Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me, 1974

William Blake, Songs of Innocence and Experience, 1789

Timothy Lai, The Obedient, 2022, oil on canvas, 182.8 x 167.6 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Barrett

In addition, Timothy Lai further uses the symbolic image of the non-human as a metaphor for those moments when he is confronted with family conflict. In Head Seat (2022), Timothy Lai portrays a sofa chair standing in a corner from an elevated perspective. The heavy cushions and the frame of the chair, which occupies the entire canvas, present a majestic and solemn aura, giving it a religious and sacred veneer under the heavy colors. As the metaphor of the “head seat”, the chair was once used as a manifestation of authority in Western art history, and in the paintings of Duchamp and Cézanne, the father sat directly on the chair to show his status. Although there is no specific figure present in the work Head Seat, its elevated perspective is evocative, only by portraying the symbolic subject, giving the image a more contextual narrative-like character, or rather, it more efficiently contains all the objects that the artist wishes to refer to and discuss through the sofa chair, which can represent authority, the throne, patriarchal structures or violent positions, all of which These intentions are simultaneously presented and equally complicated in the work, becoming the subject of a kind of concentration of issues.

Timothy Lai, Head Seat, 2022, oil on canvas, 27.94 x 35.56 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Barrett

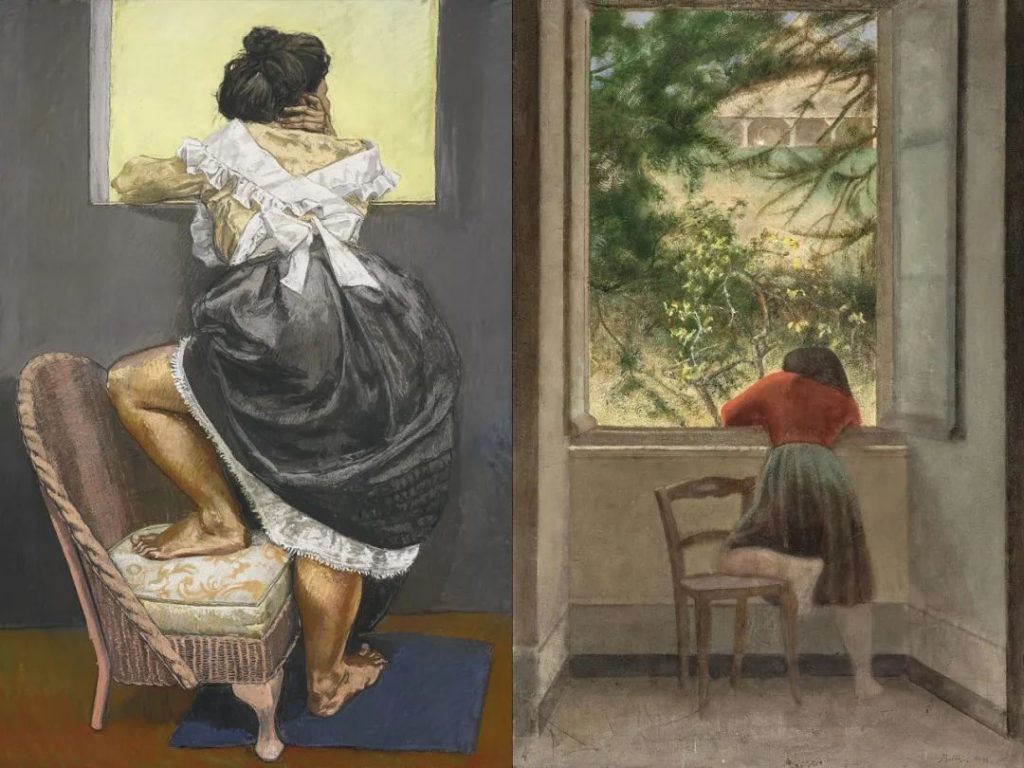

In A Space Between (2022), he deconstructs the work The Sacrifice of Abraham (1627-28) by the Italian Baroque artist Domenichino, focusing on the final moments of the sacrifice of Isaac, when the angel rescues him before his execution. In the original work, Isaac is bound to the altar in an overwhelming and substantial absence. Through this clever analogy, Lai chooses to juxtapose his own heavily patriarchal family experience with the cult of divine power highlighted in Abraham’s choice. In the work, the artist cleverly replaces the position of Isaac with that of an angel and suspends him above his father. In the picture, the son, whose back is to the viewer, is subject to the gravitational force that causes him to fall and has no place to find his personal will, but forms more interaction with his father in the structure of the picture, implying the disintegration of traditional patriarchal and religious views, which is also Timothy Lai’s position. In addition, in the work To Look, to See, to Place My Body in Relation to (2022), The image references brought by Paula Rego’s Looking out (1997) and Balthus’ Girl by the Window (1955) are also reflected in the different historical stages of Western art history, as well as the contemporary representations of the new immigrants of the globalized generation in the midst of continuous cultural integration and conflict.

Article/ Chen Yunyao

Timothy Lai, A Space Between, 2022, oil on canvas, 228.6 x 213.3 cm. Collection of Longlati Foundation. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Barrett

Domenichino, The Sacrifice of Isaac, 1627–1628, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Timothy Lai, To Look, to See, to Place My Body in Relation to, 2022, oil on canvas, 167.6 x 152.5 cm. Collection of Longlati Foundation. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Barrett

Paula Rego, Looking Out, 1997 (left); Balthus, Girl by the Window, 1955 (right)