Dust that Rides the Wind

1.

The Su’ao-Hualien Railway in eastern Taiwan and the Pacific Railway in the United States face each other across the ocean. These are monuments to the suffering of Asian immigrants and Taiwanese indigenous who migrated and labored in the global colonial past, and the fruits of man’s great ambition to transform nature after the Industrial Revolution. And these two railways are also entangled with Su Yu-Xin’s family history and her own locus of migration. In Su’s solo exhibition “Dust that rides the Wind”, the two railways, as “Water Close to Land (Coastal Road on the East Side of Taiwan)”, and “A Place of the Coming and Going (Snow Shed of CPRR Near Cisco),” are repeatedly depicted as seaside cliffs and mountain tunnels. The light illuminates the ocean as well as the road way, shinning and shifting from bright to dark, in various tones of gold and emerald.

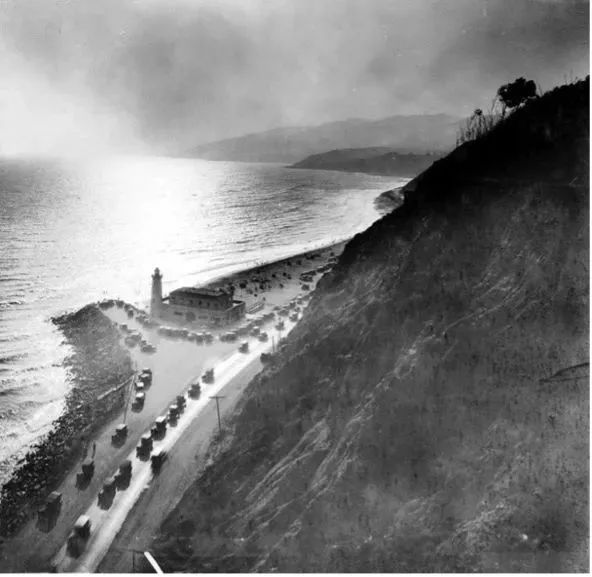

Sunset on the Pacific Ocean at the Pacific Palisades Lighthouse (near Santa Monica port) 1930

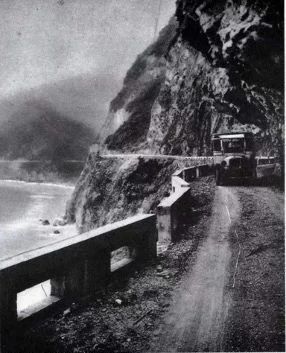

Ch’ing-shui Cliff at Hualien County, Taiwan under the Japanese rules. 1900-1930

Railroads and volcanoes, the main subjects of Su Yu-Xin’s paintings in recent years, serve as mediums in themselves, but also a pathway, a portal. One leads to the modern society where efficiency and profit are paramount, and the other to the unknown realm beyond the man-made world. Railroads, as an infrastructure-based medium, transmit efficiency and productivity with regular departures and arrivals, whether rain or shine, embodying the expectations that modern life has for productivity and convenience.

The railroads were built around the ocean, and the body of water surrounds the railroads. This imagery evokes a sense of the sublime and “oceanic feeling,” as described by Sigmund Freud. The railway is the incarnation of the modern logic of “conquest” and “transformation”, while the ocean, as the ultimate “other” to mankind, has often been imbued with a sense of sublime— the legend of the Flood spanning civilizations. Volcanoes are the exact opposite of railways: unpredictable, cannot be timed or altered, difficult to predict precisely because they operate within the peculiar natural rhythms and stay dormant for the longest time. These almost apocalyptic destructions shatter the illusion of modern life, forcing mankind to drift and flee under its threat, meanwhile giving birth to new substance in the midst of destruction. Human beings are usually at a loss in front of such a Leviathan-like primordial wonders with only awe and worship. This brings to mind Werner Herzog’s The Fire Within: A Requiem for Katia and Maurice Krafft; the two volcanologists who see the volcanoes as the only escape from the mediocrity and narcissism of the human world. And in La Soufrière the old man who refuses to leave when the volcano is about to erupt. The gaze connecting the railroads and the volcanoes calls attention to the battle between the Apollonian and the Dionysian. Human beings are never satisfied with defining themselves in terms of the subject-object duality, but they also cannot stop the compulsive effort to separate the subject from the object. Modern mankind is constantly searching for anchorage in the entanglement of these two forms of self.

Most of the landscapes in Su’s works have specific site references in reality, but they are abstracted into a unified schema in their sequential unfolding—a tunnel on a cliff by the sea awaiting the train to pass through, a volcano in eruption—a meta-image.

Werner Herzog, La Soufrière, film still.

2.

The paintings in the exhibition are interconnected in terms of materiality, subject matter and the specific landscape they represent. They are paintings of the medium, escaping from the framework imposed by modernity on paintings. The problem of the subject-object is temporarily reconciled here through the urge to establish connections. Movement/migration, as well as the methodology of color are the two important threads which bind them.

Here the tendency of movements is not only expressed through the subject matter, but also in the impending momentum manifested in the paintings; these passages, road imagery or volcanoes in eruption are effectively emphasized in the pictures in terms of their impulse to move or be passed through. The color blocks and color fields in the pictures are often dominant, while the lines under-guard the movement, forming a rebellion against the line-scribing and color-filling tradition. The dynamics in the volcanic works are even more evident. Cloud Nest is covered with layers of clouds, only distinguished by their colors, even the land is simulated by clouds. In Smoke Engulfs, the lines depicting smoke resemble the lines frequently used to denote movement in comic books, with unknown substances escaping from within. A stroke of purple overlaps the railway in Passage of Pink, and the seemingly chaotic lines lift the bubble-like color fields, creating a real surge of movement in the tranquil scene of the railway. At the same time, the force of movement is evident in both gestures as well as brushstrokes: the cliffs in Water Close to Land resembling blades, sleek curves in Honey that flow slanting across the panel — the mountains are moving, yet the clouds remain still. The borders between the cliffs, and the clouds or the sea are deliberately blurred, and a few clouds seem to be suspended above surface of the sea in Water Close to Land. The Pacific Railway series are frequented by color blocks, anchored by the few strokes depicting railroad tunnels, lighthouses at the end of the road, and power poles.

The treatment of “unpaintable subjects” in Yuxin’s works also provides inspiration for the presentation of “movement”. Both Mountain of Gold (Ch’ing-shui Cliff) and Water Close to Land (Coastal Road on the East Side of Taiwan) were done with mostly blue and yellow, and the “virtual” light beam in Mountain of Gold (Ch’ing-shui Cliff) intentionally separates the subject and its shadow in a wrong way, forming a trompe l’oeil effect—the mountains blue like the ocean, and the sea yellow like the sun. The rocks in Water Close to Land (Coastal Road on the East Side of Taiwan) were depicted with earth-like yellows, and the shadow of the mountain with ocean-like blue. While the landscapes in Hill Front and Back Hill appear to be static, the change of skylight is compressed in the background, and the flow of time presented with square color blocks in a diagram-like manner. In this way, different kinds of speed and momentum of the subjects manifest themselves: the accelerated travels in the age of steam, as well as the sometimes slow, other times explosive movements in nature.

3.

The earliest pigments in history came from natural substances that were readily available. As the modern chemical industry developed, colors and pigments had been greatly enriched and started to circulate the globe accompanying human migrations. Art history witnessed every moment a new kind of paint was invented. Early as in Theaetetus, Plato used the correlation, fluidity of color, and relationship between color and its viewers as examples to make a wise statement about knowledge: “When the eye and the appropriate object meet together and give birth to whiteness and the sensation connatural with it, which could not have been given by either of them going elsewhere, then, while the sight is flowing from the eye, whiteness proceeds from the object which combines in producing the colour; and so the eye is fulfilled with sight, and really sees, and becomes, not sight, but a seeing eye; and the object which combined to form the colour is fulfilled with whiteness, and becomes not whiteness but a white thing, whether wood or stone or whatever the object may be which happens to be coloured white…there is no one self-existent thing, but everything is becoming and in relation.” The development and naming system of modern color theory brings us the impulse to abstract colors when we look at paintings. The artist Amy Sillman wrote, “Art historians might have beheld colors, but never held color.” We as audience or writers, do not actually possess embodied experience or perception of everything which came before the paintings’ formation—the prehistory of painting. The writing of art has such a hard time reaching their destination.

Yet the pigments on the canvases do not shy away from pointing out their origins through the colors they manifest; the lapis lazuli in Water Close to Land (Coastal Road on the East Side of Taiwan) came from Afghanistan, known by us by the name of ultramarine. The extraction of this pigment was so difficult that it was sometimes more expensive than gold. Artists’ infatuation with this pigment led to the creation of chemically synthetised ultramarine; the quest to discover a synthetic ultramarine capable of simulating the texture of the natural mineral became an obsession for Yves Klein. The carmine used in Water Close to Land (Coastal Road on the East Side of Taiwan) is obtained from cochineal insects found in Peru. The insects live on cacti; their newly-hatched bodies present a striking magenta, used for centuries to dye cloth and make cosmetics, even to decorate food. The sulphur used in Mountain of Gold (Ch’ing-shui Cliff) was collected in Jiufen and Jinguashi, Taiwan. Today the gold mines at Jinguashi are no longer active but the sulphur associated with them still remain aground. Sulphur is also commonly found within volcanic massifs, rising at the moment of crustal impact, known sometimes as “devil’s gold”. Red is iron, green is copper, and clay is a mixed white, come from various sources including ore or ground organisms. Despite color’s complex identities and origins, today their histories have sunken into obscurity and they are known mostly as CMYK values. Cochineal and lapis lazuli from exotic lands; conch shells; coral skeletons of unknown ages; Shanghai spring mud collected from 2022; gathered together in a mixed symbiosis and brought into the studio to be ground into powders, poured into crucibles, dissolved in water then boiled with binders, and then blended with other pigments and applied to the panels. In this way, the pigments and the subjects in the painting become intertwined through their shared history. The pigments bring their physical presence into the painting, becoming as much a protagonist as the landscape.

Colors have always been on the move and the meanings they carry have never stopped changing. Colors, and the materials or objects that bear them, are associated with their functions in the eyes of humanity and become physical representations of the latter. In ancient mythology, black is associated with primal chaos, but over time it became seen as symbolizing productive capacity – first with the fertile soils of the agricultural age, then with the coal of the industrial era, and finally with oil and asphalt in the post-industrial age. Then as modern painting obtained a wider reach, black was seen to be one of the most representative colors of modernism in art, literature, and fashion design. In ancient matrilineal societies, red originally represented vitality, fire and blood; then later during the long ages of patriarchy, it evolved into a symbol of death and sacrifice brought by war and violence. The political significance it gained in the twentieth century is self-explanatory. In this way, colors are imbued with meaning and those meanings are often wrapped in ideology. In the artist’s essay A Color Study Leading Towards Materialism, Su Yu-Xin discusses how linguistic system shapes the way people perceive color, creating a kind of politics of perception. The process of human perception was originally an intuitive mechanism, as Freud made the iceberg of subconsciousness apparent, against the backdrop of neoliberalism and contemporary political developments, human perceptions have become an object that can be “managed”. And “perception management”, a strategy that is not without its sinister connotations, has become a real sorcery of post-modern society, gaining popularity in the global political and economic system.

Extracting lake pigment from Lithospermum in the studio

Collecting ochre at 3500 meters above sea level in Yunnan Province, China

Su Yu-Xin has made her expeditions collecting raw materials from around the globe into color swatches that resemble both diagrams and landscapes. Here, colours are no longer mere visual signifiers stripped of their origins and histories, arranged in neat order on the color wheel, naming themselves according to their scientific values such as RGB and CMYK, brightness and saturation. They are the embodiment of the remains of once living beings, of minerals, clays and dust; they are the children of mountains, rivers, lakes and seas, narrating their characters, histories, homelands and journeys on panels the size of books. During the evolution of our planet’s material civilisation, some of them have become molecules that have entered into our bodies, “evolving” to become parts of the human body; others have become “natural resources” to be “gathered” and “extracted” in various forms. With them we share a similar material origin – and perhaps a similar fate. Su Yu-Xin’s work can be seen as a kind of molecular realism, where art becomes a chapter of natural history.

Luan Shixuan

About the Curator

Luan Shixuan currently serves as a curator at UCCA Center for Contemporary Art. She has curated exhibitions including “Wang Tuo: Empty-handed into History” (2021), “Elizabeth Peyton: Practice” (2020), “After Nature: UCCA Dune Opening Exhibition” (2018), and organised shows including “Diriyah Biennale: Feeling the Stones”(2021), “Matthew Barney: Redoubt” (2019), “Sarah Morris: Odyssey” (2018).